Russia’s de facto annexation of Crimea marks a twenty first century turning point, carrying with it as many messages for the Caribbean as it does for Europe and the United States.

It indicates in a profound way that the post-Cold War desire by members of the G7 – the world’s wealthiest nations – to expand unchallenged their global influence, may be coming to an end. It suggests a world with a new military and political balance and a more abrasive multi-polarity is about to emerge.

Irrespective of how concerning or wrong Russia’s decision to protect its own interests by controlling territory, albeit belonging previously to the former Soviet Union, events in Crimea have made clear that Russia will not be passive and let the future benefit the US and Europe alone.

For years now, Russia, China and others have been saying that Western expansionism, its willingness to intervene in other nations, and its desire to impose western norms of democracy, social behavior and aspiration, is destabilizing nations that have very different histories and cultures.

Their belief has been that while there are many common global threats that require consensus based solutions, nations must find their own way forwards. This, they believe, requires an approach in which national strategic interests are respected in order to maintain integrity and an equitable global balance.

Mr. Putin could not have been clearer. Recalling last week what the West did in Yugoslavia, Iraq and Libya, at a Moscow press conference, he accused the US of encouraging anarchy.

“I think they sit there across the pond in the US, sometimes it seems … like they’re in a lab and they’re running all sorts of experiments on the rats without understanding consequences of what they’re doing.” “Why would they do that? Nobody can explain it,” he said.

While it is equally possible to interpret this as a smokescreen for cynical opportunism on the part of the present Russian leadership or a reflection of Mr Putin’s desire to restore Russia’s greatness in the minds of a people tied by a shared history to the Czars, commissars, holy Russia and their sacrifice in Stalingrad, events in Crimea make clear Russia again expects to play a global role.

Russia’s determination is driven by a sense that the west has become weak, has mixed objectives, and is dissolute. It sees Europe driven by a fear of economic collapse and a loss of global economic power; the electorates of Europe and the US having no appetite for war as a result of its leaders’ unnecessary adventures in Iraq and Libya; and the US leadership vacillating and lacking the will to confront.

As a consequence what now appears to be happening is that a long period of western expansionism is coming to an end and a hardened response from Moscow and most probably China will be something that the G7 will have to become accustomed to.

This is not to suggest that Russia is as strong economically and technologically as the west but to recognize a significant change in global dynamics to which the Caribbean will have to adapt.

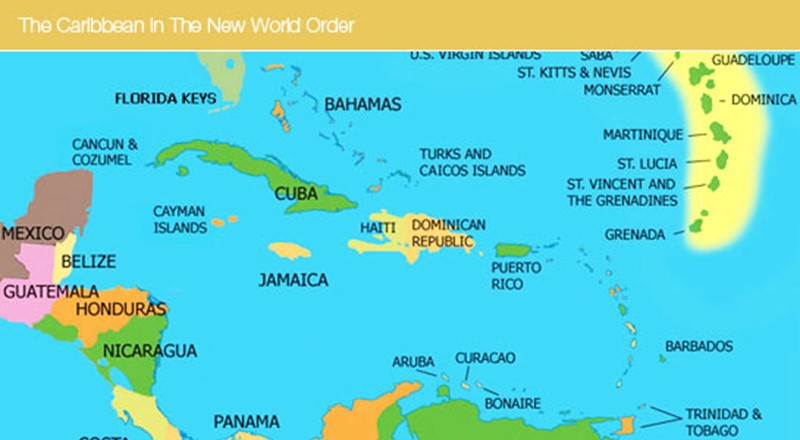

For the Caribbean and Latin America, there are multiple messages in all that has happened in the last week.

Firstly, Russia’s changed profile challenges the US’s geo-strategic and military pivot to the Pacific and potentially its recent declaration that the Monroe doctrine in the Americas is at an end. Russia has already made clear through its new global naval strategy and recent demonstrations of its naval and air capabilities across the Caribbean Basin that it intends having a presence and role in the region. Its far-reaching re-engagement with Cuba does the same.

Secondly, Russia’s new-found willingness to confront what it does not agree with restores geography to paramountcy in foreign relations; placing an emphasis on spheres of influence, sea lanes, the Panama Canal and the need to understand the detail of national and regional dynamics. It will modify the belief prevalent since the end of the Cold War that regions like the Caribbean that are regarded as marginal, only need addressing generally, through cross-cutting themes such as social rights, the environment, and prosperity.

Thirdly, it will over time enable larger Caribbean nations to more strongly assert their role in the world, choosing judiciously how to leverage what they want through well deployed arguments that resonate with new concerns.

Fourthly, it makes new political constructs like the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC) a voice that can have greater political resonance with the United States, Canada and Europe.

Fifthly, from a regional perspective it may raise questions in Havana as to how it can now balance its deepening relationship with a potentially resurgent Russia, its already close relationship with Nicaragua, Venezuela and the countries of the Caribbean Sea, and its genuine desire for an improved relationship with the US.

Sixthly, it suggests that the idea emerging in Europe and North America that there is a need to embrace China in the development and restoration of prosperity in the countries of the Caribbean Basin may be subject to revision.

And finally, in a by no means exhaustive list, it will consolidate NATO and the transatlantic alliance, and see the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) rapidly progress to a successful conclusion.

Speaking in Washington before Christmas to an academic about new influences in the Caribbean, we agreed that what nations like Russia, China and others have been doing in their economic engagement with the region is genuinely beneficial; but we also noted that this help put down markers with an eye to the strategic value that a presence in the Caribbean might have in the longer term.

This is not to suggest that the world is reverting to a Cold War but to recognize that when the dust has settled and a strategic and hard headed assessment takes place, the Caribbean Basin will again be a small but important factor in the global considerations of larger powers.

The nations and islands of the Caribbean lie in the stream of history. What is now needed in the region is quiet contemplation of how, within these new parameters and the friendships the region has created over the last two decades, a now largely services oriented region is going to position itself politically.

David Jessop is the Director of the Caribbean Council and can be contacted at david.jessop@caribbean-council.org. Previous columns can be found at www.caribbean-council.org.